Component deltas for less painful handoffs

When proposing new designs to existing digital products, communication gaps between design and engineering can slow things down.

The process often goes like this:

Designer creates a set of wireframes or comps with a new feature or user workflow. Stakeholders review, excited to incorporate into the product. Those are forwarded to engineers who now need to figure out how to incorporate these new features and flows into an existing site or application.

Before engineers can start to build, they have to think through:

- How similar to existing components are the components proposed in this wireframe/comp?

- Should this be a new component or a variant of an existing one?

- If this component should be a variant, what additional features do I need to incorporate? Do I need to extend existing behaviors and options or include new ones?

- If the proposed design and behavior is unique enough to warrant a new component, do I have a clear understanding of the expected behavior and design? What are the bounds of available options? What layers of abstraction are warranted here?

This is the subtle art of engineering: striking a balance between abstraction and complexity.

The Challenge: Unclear Expectations or Requirements

The answer to these questions may not be obvious, even with good documentation. This is often where gaps spring up, between the “dreaming up” and “building out” phases, and cause a lot of overhead and increasing the time to market.

Some orgs have tight integration between design and engineering teams, with detailed processes for making these decisions together. But handoffs like the one I described are still a reality for many orgs.

Once the engineering team receives designs, two scenarios are common:

- Engineers send the request back to the design with a set of clarifying questions. This introduces unanticipated delays and makes it challenging for project managers to track responsibility and ownership of the task.

- Engineers make assumptions about behavior or functionality because of gaps in communication, resulting in a finished product that doesn’t align with what design envisioned or stakeholders expected. Work has to be undone and redone.

A Solution: Documenting Component Deltas

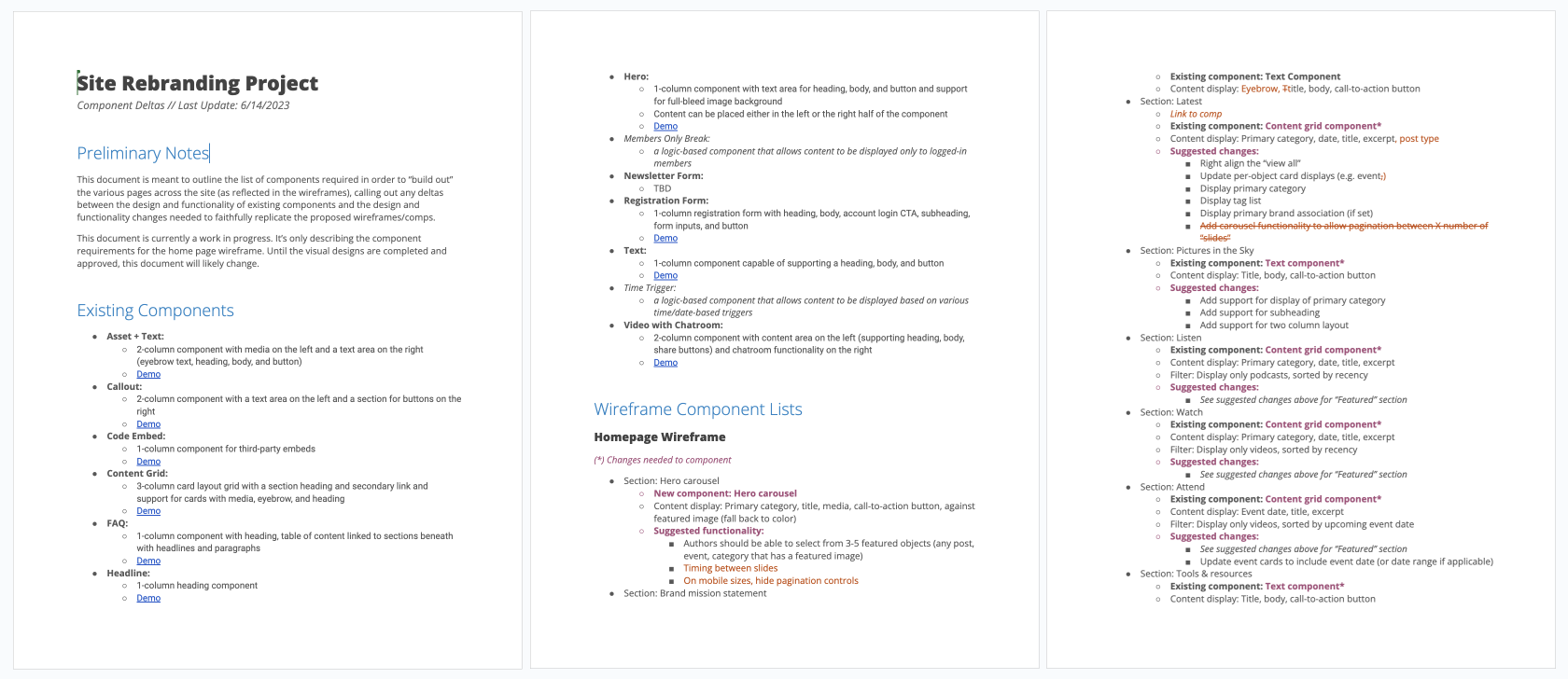

One of the tools I often use to improve communication between design and engineering teams is what I call a “Component Deltas” document. It’s a record of variations between proposed designs and existing components. The goal of the document is to quickly identify “what exists” and connect that to “what needs to be built.”

This document should outline the list of components required in order to “build out” the various pages across the site (as reflected in the wireframes or visual prototypes). It should call out any deltas between the design and functionality of existing components and the design and functionality changes needed to faithfully replicate the proposed designs.

The format of the document can vary based on your team’s specific needs. I drop it in whatever shared text editing tool most of the team has access to (e.g. Google Docs). It should include a few key pieces of information:

- Existing component name

- Description

- Existing design characteristics vs. expected design characteristics

- Existing behavior vs. expected behavior

- Visual indicator that a change is required (star, bold, whatever works)

Ideally, you can also include links to a demo of the component in your existing styleguide or component library. Whatever helps get everyone on the same page about what currently exists and what is being requested.

This can be a supplement to other documents. For example, I’ve often paired this with a spreadsheet that contains each of the requested component changes. It helped engineering team track more aspects, like behavior at specific breakpoints, variant characteristics, level of effort to build, priority, and whether or not its a new component.

Which team owns this document will depend on your team’s structure, but the output should be the result of close collaboration between design and engineering teams, answering the questions listed above. Ideally, common naming schemes across all teams will reduce friction and make this collaboration even better.

—

Cheers,

Up Next: Do your job.

Design Systems Daily

Sign up to get daily bite-sized insights in your inbox about design systems, product design, and team-building:

New to design systems?

Start with my free 30-day email course →